This month, Nvidia rolled out what might be one of the most important updates for its CUDA GPU software stack in years. The new CUDA 13.1 release introduces the CUDA Tile programming path, which elevates kernel development above the single-instruction, multiple-thread (SIMT) execution model, and aligns it with the tensor-heavy execution model of Blackwell-class processors and their successors.

By shifting to structured data blocks, or tiles, Nvidia is changing how developers design GPU workloads, setting the stage for next-generation architectures that will incorporate more specialized compute accelerators and therefore depend less on thread-level parallelism.

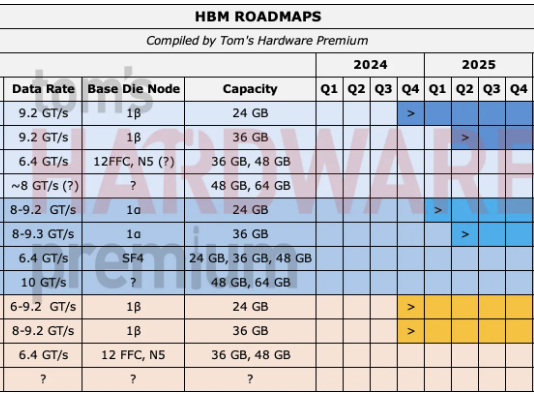

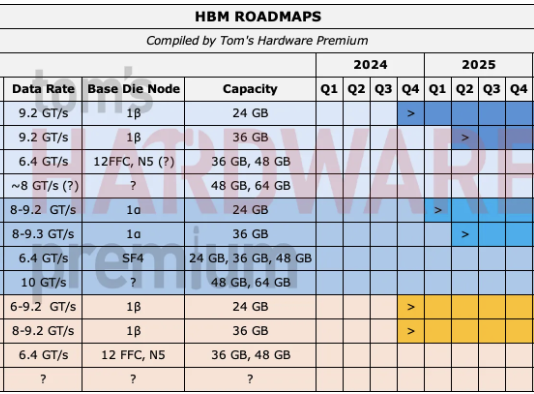

Tom’s Hardware Premium Roadmaps

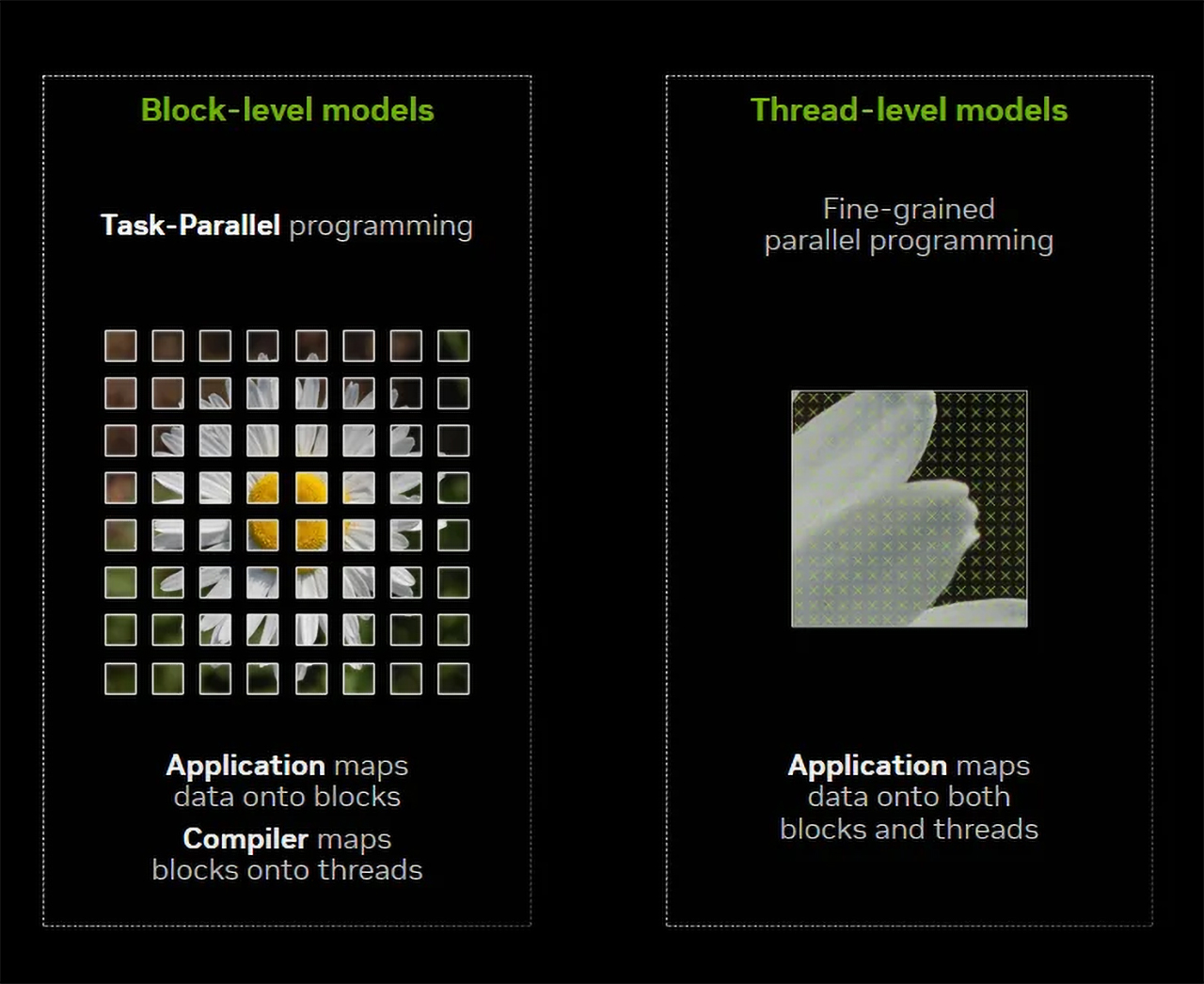

SIMT vs. Tiles

Before proceeding, it is worth clarifying that the fundamental difference between the traditional CUDA programming model and the new CUDA Tile is not in capabilities, but in what programmers control. In the original CUDA model, programming is based on SIMT (single-instruction, multiple-thread) execution. The developer explicitly decomposes the problem into threads and thread blocks, chooses grid and block dimensions, manages synchronization, and carefully designs memory access patterns to match the GPU’s architecture. Performance depends heavily on low-level decisions such as warp usage, shared-memory tiling, register usage, and the explicit use of tensor-core instructions or libraries. In short, the programmer controls how the computation is executed on the hardware.

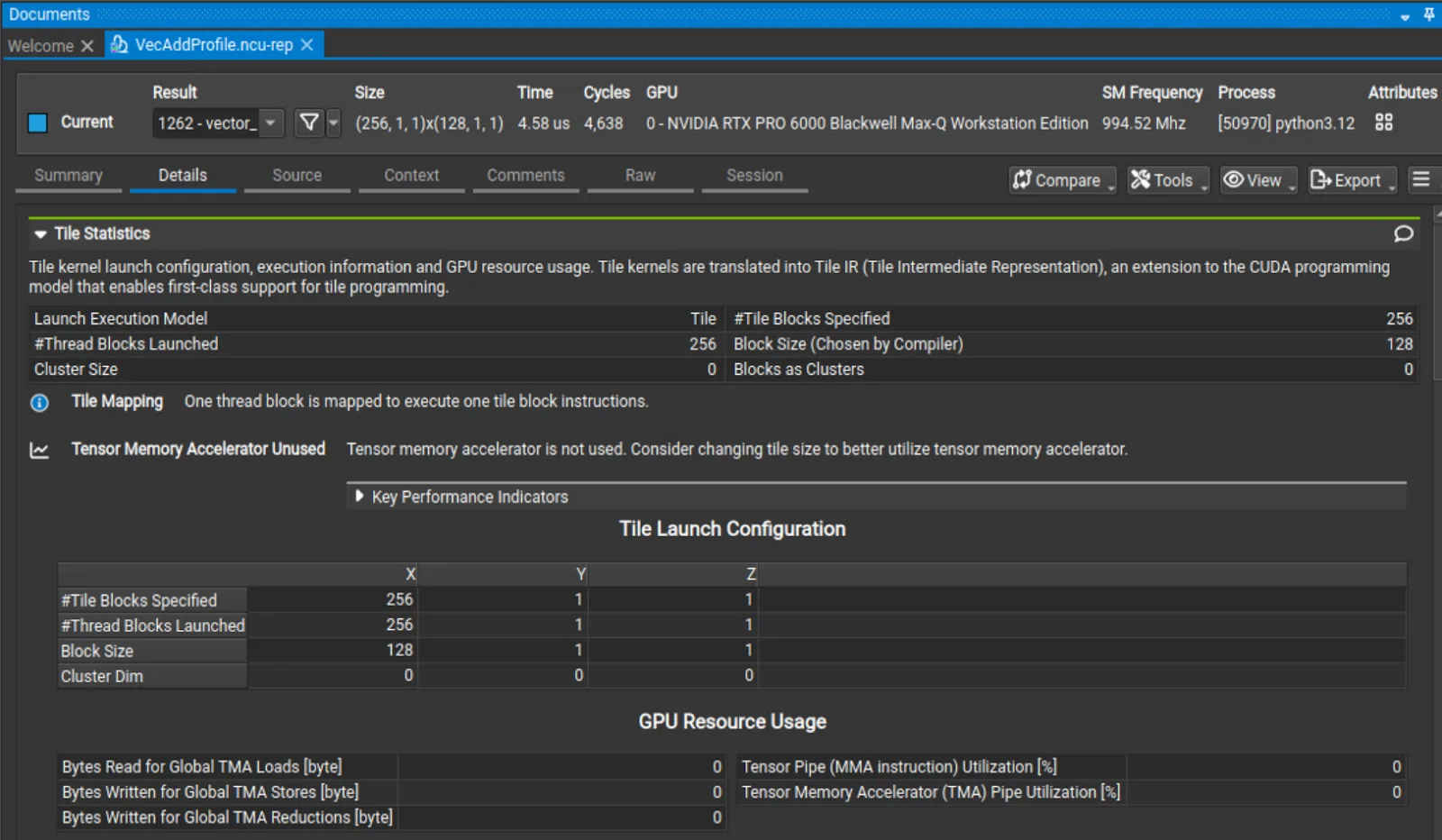

CUDA Tile shifts programming to a tile-centric abstraction. The developer describes computations in terms of operations on tiles — structured blocks of data such as submatrices — without specifying threads, warps, or execution order. Then the compiler and runtime automatically map those tile operations onto threads, tensor cores, tensor memory accelerators (TMA), and the GPU memory hierarchy. This means the programmer focuses on what computation should happen to the data, while CUDA determines how it runs efficiently on the hardware, which ensures performance scalability across GPU generations, starting with Blackwell and extending to future architectures.

A strategic pivot in the CUDA Model

But why introduce such significant changes at the CUDA level? There are several motives behind the move: drastic architectural changes in GPUs, and the way modern GPU workloads operate. Firstly, AI, simulation, and technical computing no longer revolve around scalar operations: they rely on dense tensor math. Secondly, Nvidia’s recent hardware has also followed the same trajectory, integrating tensor cores and TMAs as core architectural enhancements. Thirdly, both tensor cores and TMAs differ significantly between architectures.

From Turing (the first GPU architecture to incorporate tensor units as assisting units) to Blackwell (where tensors became the primary compute engines), Nvidia has repeatedly reworked how tensor engines are scheduled, how data is staged and moved, and how much of the execution pipeline is managed by warps and threads versus dedicated hardware. With Turing, tensors were used to execute warp-issued matrix instructions, but with Blackwell, things shifted to tile-native execution pipelines with autonomous memory engines, fundamentally reducing the role of traditional SIMT controls.

As a result, as tensor hardware has been scaling aggressively, the lack of uniformity across generations has made low-level tuning on warp and thread levels impractical, so Nvidia had to elevate CUDA toward higher-level abstractions that describe intent at the tile level, rather than at the thread level, leaving all the optimizations to compilers and runtimes. One bonus to this approach is that it can extract performance gains across virtually all workloads throughout the active life cycle of its GPU architectures.

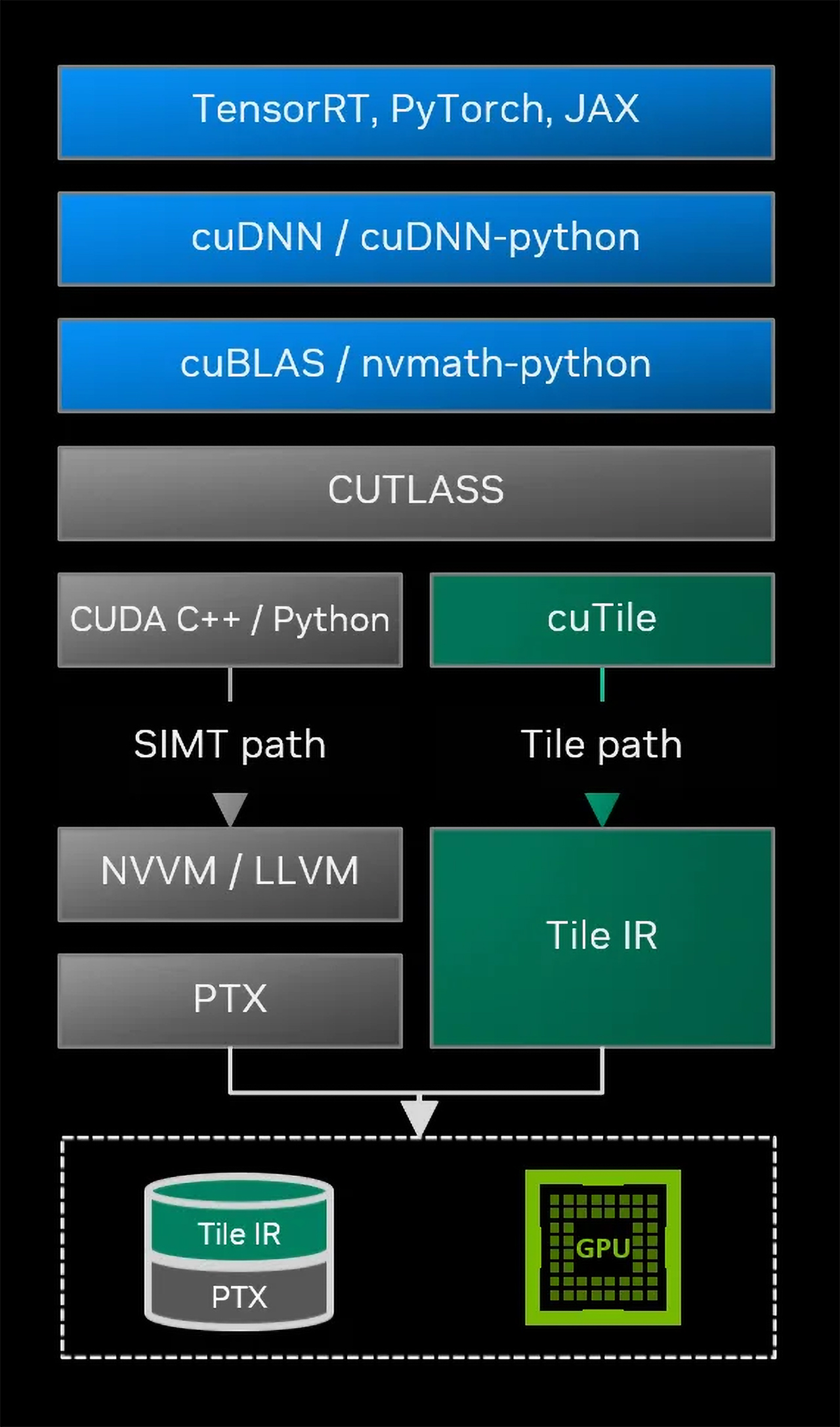

Note that it does not abandon SIMT paths with NVVM/LLVM and PTX altogether; when developers need them, they can write appropriate kernels. However, when they need to use tensor cores, they must write tile kernels.

CUDA Tile: How does it work?

At the center of this new CUDA Tile stack sits CUDA Tile IR, a virtual instruction set that plays the same role for tile workloads that parallel thread execution (PTX) plays for SIMT kernels. In the traditional CUDA stack, PTX serves as a portable abstraction for thread-oriented programs that ensures that SIMT kernels persist across GPU generations. CUDA Tile IR is designed to provide that same long-term stability for tile-based computations: it defines tile blocks, their relationships, operations that transform them, but hides execution details that can change from one GPU family to another.

This virtual ISA also becomes the target for compilers, frameworks, and domain-specific languages that want to exploit tile-level semantics. Tool builders who previously generated PTX for SIMT can now create parallel backends that emit Tile IR for tensor-oriented workloads. The runtime takes Tile IR as input and assigns work to hardware pipelines, tensor engines, and memory systems in a way that maximizes performance without exposing device-level variability to the programmer.

In addition to Tile IR itself, CUDA 13.1 introduces another key component to bring CUDA Tile to life: cuTile Python, a domain-specific language that allows developers to author array- and tile-oriented kernels directly in Python.

For now, development efforts are focused primarily on AI-centric algorithms, but Nvidia plans to expand functionality, features, and performance over time, as well as to introduce a C++ implementation in upcoming releases. Tile programming itself is certainly not limited to artificial intelligence and is designed as a general-purpose abstraction. As Nvidia’s CUDA Tile evolves, it can be applied to a wide range of applications, including scientific simulations (on architectures that support the required precision), signal and image/video processing, and many HPC workloads that decompose problems into block-based computations.

In its initial release, CUDA Tile support is limited to Blackwell-class GPUs with compute capabilities 10.x and 12.x, but future releases will bring support for ‘more architectures’ though it is unclear whether we are talking previous-generation Hopper or next-generation Rubin.

Setting the stage for Rubin, Feynman, and beyond

With CUDA Tile, Nvidia is reorganizing the CUDA software model around tensor-based execution patterns that dominate modern workloads. Traditional CUDA Tile will coexist with the proven SIMT model, as not all workloads use tensor math extensively, though the vector of industry development is more or less clear, so Nvidia’s focus will follow it.

Nvidia’s CUDA Tile IR provides abstraction that enables architectural stability needed for future generations of tensor-focused hardware, while cuTile Python (and similar languages), as well as enhanced tools, offer practical paths for developers to transition from SIMT-heavy workflows.

Combined with expanded partitioning features, math-library optimizations, and improved debugging tools, CUDA 13.1 marks a major milestone in Nvidia’s long-term strategy: abstracting away hardware complexity and enabling seamless performance scalability across each GPU generation.